Hello, Nathan, we hope you are well. Please briefly tell us about yourself.

First and foremost, I am a 52-year-old father and husband. I am also an English teacher at a community college in San Francisco, California (in the United States), the city I was born and raised in. Finally, I am a simple photographer who has used whatever equipment I can afford so that I can try to capture silence.

What or who got you started or inspired you in your photography?

Before I ever started the serious practice of taking my own photographs, I was fascinated by the classic greats of black and white photography such as Edward Weston, Paul Strand, Imogen Cunningham, Minor White, Wright Morris, Ansel Adams, and many others. Like most modern human beings, I had, for most of my life, been taking photographs to preserve memories of times spent with family and friends as well as the places I visited on vacation. I, of course, did not have a cell phone camera that allowed me to photograph every single minute because they were not available, so I used film cameras and had my images processed at a photo processing store. It wasn’t until 2007 that I first began to take photography seriously— after purchasing my first DSLR camera: a Sony Alpha 100. I was still mostly interested in classic black and white photography. Very soon after I learned the basic operations of my camera, I discovered long exposure photography through the many, very-talented artists who were posting their work on Flickr. Soon after that, I discovered the work of Michael Kenna, and I have been hopelessly and happily hooked on finding new ways to use long exposures ever since. In 2013 I began experimenting with an infrared converted camera.

But my primary focus has always been on black and white photography. Color photography can be quite wonderful, and I really enjoy looking at color images, but I have only minimal interest in working on color for myself. I see the world in color. I do not wish to create images in the way that I already see.

In fact, I have always wished I could paint. My mom was an excellent painter, but I did not inherit that talent from her. I know that photography is the process of painting with light, and I am grateful that I have found a way to express my creative impulses with these tools, but I have always loved the disciplines and freedoms of painting. I also wish I had the talent to write a very good poem, but I do not. I studied poetry very deeply as an undergrad and a graduate student (I have a BA and MA in English Literature)—and I continue to do so. I suppose my inability to paint or write good poems led me to photography as well. Much of what I do is influenced by my studies of and appreciation for both those mediums (and my love for the cinema).

Finally, I have always felt a deep affinity with the sea, with the rocky shorelines of the West Coast of the United States— as well as the forests and lone trees growing in the grassy hills and farmlands of California, so I have naturally gravitated towards photographing those places and subjects. After all, photographing them affords me the opportunity to both pursue a practice of photography and continue to spend time wandering around in nature.

I would like to know how you describe minimal photography and what minimal photography means to you?

Historically speaking, minimalism in art, especially from the perspective of critics and curators, tends to refer to creating pieces that provide the viewer an opportunity for a response grounded purely in the visual experience of seeing the work. Often this means that the artist did not seek to express anything about him or herself in the work, the work only being a reflection of the work itself. The creation is, in the end, determined by its medium and the materials used to create it. This does not seem to be what minimalism currently refers to in 21st century “minimal photography.” Instead, we seem to mostly be speaking of reducing the elements included in a photograph. We tend to think of it as “minimalistic,” as in having few elements in the image.

But your question is not about such things; it is about what I think it means. In all honesty, I do not think about it much while I am creating. Everything I photograph tends to be focused on a single thing or, at most, a few simple things. In the end, when I take the time to really think about it, I suppose I think true minimalism should be reserved for those images that have very little “form” in them. I do have a small series of images in which the focus is mostly on the simplest of things— such as a shoreline with nothing but water, sand and sky. I suppose, in a way, I see that as a practice of reducing the subject down to a truer sense of “less is more,” such an approach allowing one to express the tonality in interesting ways since the eye can only focus on a minimal amount of forms such as the presence of light. Most of my work is “minimalistic” in nature, but I do think my work is truly an expression of minimalism.

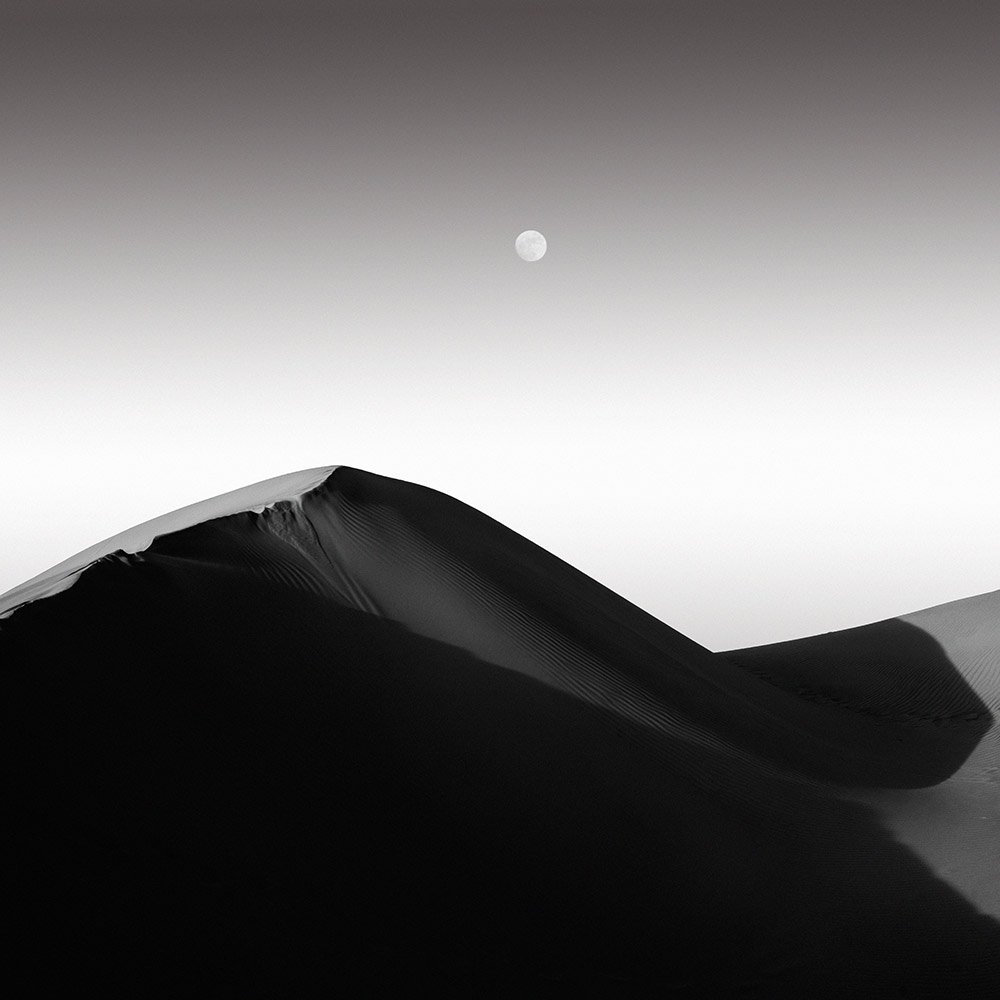

However, I do not really think about such things very often—or maybe I did in the past as I was developing my practice of photography, but I no longer do. Perhaps a more helpful way to explain my thoughts about such things would be to discuss the Japanese spatial concept of ma. This is something I have been pondering for a while. When we speak of using minimal subject matter in a photo, we are often thinking about negative space. Simply stated: negative space, from a design perspective, is the space that surrounds and flows between the subject of an image. This is certainly a useful design principle to consider as one develops how one might wish to compose a photograph—and I think this is what is at the heart of the thousands of tutorials that offer negative space as a way to consider how and what you contain within the frame of an image. The Japanese spatial concept of ma, on the other hand expresses this in even more interesting, meaningful and valuable ways. While it is difficult to define such a concept in a few choice and illuminating words, one can begin to conceive of ma’s principles by pondering it as a consideration of seeing, hearing and, perhaps, feeling and expressing (a) the intervals and emptiness of space; (b) the void between all things; (c) a pause in time; and (d) a simultaneous experience of form and non-form.

Ma speaks as much of what is not there, what is not said or expressed, as it does for what is there. Ma provides an intriguing perspective for entering the space between notes in music; the spaces between the flowers and the branches in an ikebana arrangement; the pauses within a poem; the space left unbrushed in calligraphy and brush paintings (the non-form of the empty space ending up preserving the movement(s) of the brush when the calligrapher swooshed ink across the empty white space); the experience of the non-form, whether conscious or unconscious, bound to the experience of the form and the experience of the form bound to the non-form.

But, ultimately, ma is not a conscious application of a design principle on the part of the artist— nor is it exactly a conscious realization by its viewer (I cannot, for example, imagine a viewer saying “this image needs more ma” or the artist saying “today, I am going to use some ma to create an image”). Ma can certainly be spoken of and used to explain facets of a creation, but the creative impulse is often far more grounded in “the spontaneous act of creation” than “a planned act,” far more grounded in “an unconscious engagement with art” than a “conscious application of a principle to an experience.” In other words, any conscious application of ma falls short of explaining the experience of it. One can, upon reflection, certainly ponder such ideals but the experience and act of ma ultimately transcends any awareness of ma. It speaks of something beyond intent or specific understanding, coming instead from something within a creator or viewer, for it resides in the spaces between; it resides in silence.

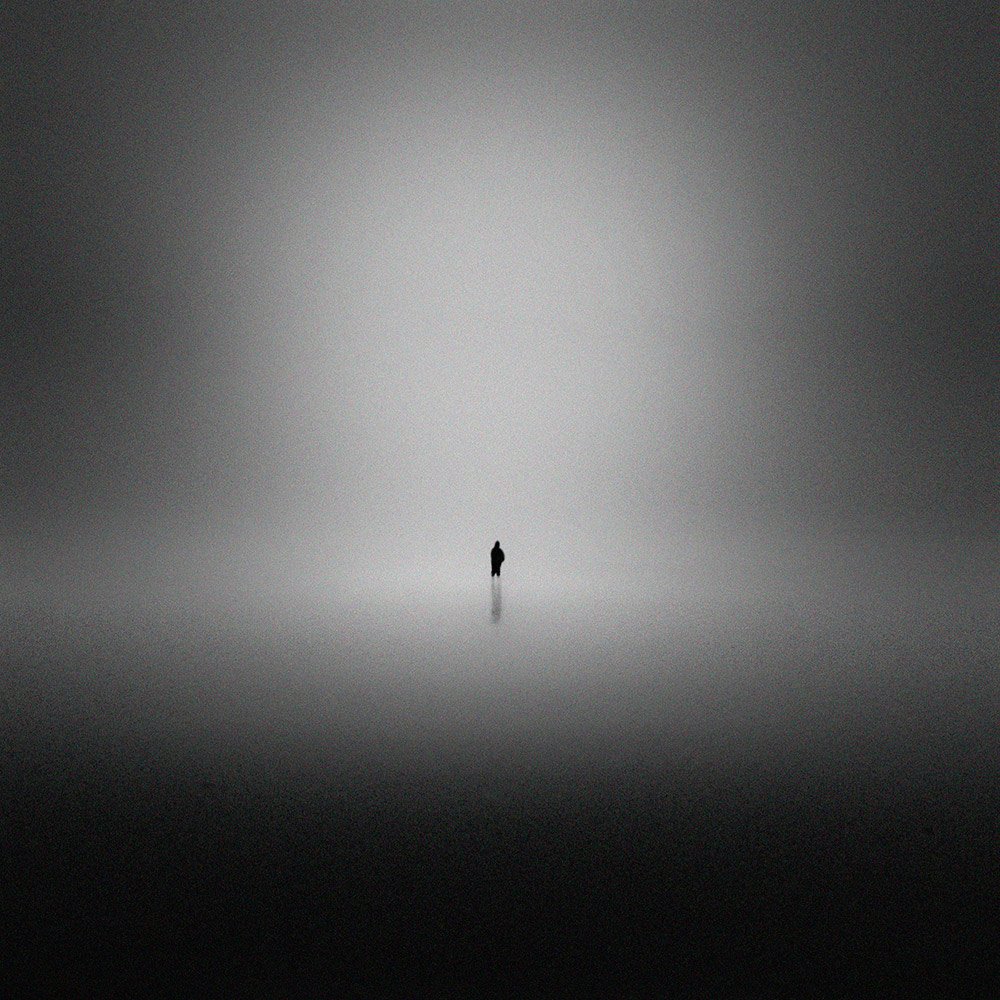

And if I must utter what photography is about for me, it is about invoking silence.

What gear do you carry with you on your photo shoots, especially when shooting snowy landscapes?

I have, on a few occasions, photographed when there is snow on the ground, but it does not snow where I live (lots of rain, but no snow), so I do not often have the opportunity to photograph snowy landscapes. Second, I carry whatever gear I currently own—which is whatever gear I have been able to afford over the years. I do not pay very much attention to the latest gear. I buy something used and then when it ceases to function, I stop using it. That said—I tend to bring the following equipment:

Cameras: (1) Sony a99 for long exposure work (2) Infrared converted Sony aR7 for trees

Lenses: (1) Tamron 24-70 (2) Minolta 17-35 (3) Sony G series 70-300 (4) Minolta 50mm

Filters: (1) Lee Little Stopper, Big Stopper and Super Stopper (2) Lee Grads (3) Breakthrough Photography Infrared filter

Other: (1) a loupe (2) an intervalometer (3) a cloth to wipe my lenses

What Is your favorite website or blog you visit often?

I am guessing that this should be a photography blog or website. I do not frequent many of them. I do really enjoy looking at the work displayed at Art Limited and Dodho—both of which offer a viewer a very eclectic selection of all the photographic genres.

Is photography considered as art? If yes, explain please.

That is a seemingly simple question that can be quite complicated. In short, yes, I think photography can be considered art (and some of it should be considered art). However, does it really matter if it is? Who is in charge of such determinations? Does the final answer to this distinction belong to collectors? Art critics? Museum and gallery curators? The eye of the beholder? Does saying that “it is art” make it “art”? Does saying that “it is not art” make it “not art”? Does offering a compelling argument for or against it change what it is?

The more complicated response begins with the fact that art can refer to many things, and the two most important to this question, in my humble opinion, are (1) the expression and creation of something, often bound to certain aesthetic principles, that is considered beautiful, appealing or beyond ordinary significance and (2) the mastering of a skill. These definitions are, at best, overgeneralized and far too limited, but they should encapsulate the basics.

To begin, photography has long been thought by many critics to not be worthy of the same critical attention as painting, sculpture or drawing and has thus been set aside as a lesser expression in the field of the visual arts. Many critics scoffed at it as being little more than capturing something as it is— much of the critique, I assume, being based in a perceived lack of a true creative skill—a painter, for example, being praised for mastering the use of materials and honing a creative eye in order to create a “seeming something” from nothing by using one’s inherent talents. The photographer, on the other hand, was thought to be doing little more than pointing a box at something and clicking the shutter and then using some chemicals to wash the material into existence (and nowadays many are criticized for just using Photoshop).

I mention this because I think the central crux of the question comes from a disagreement about whether photography utilizes a creative skill-based practice. Such a perspective has serious ironies because another big question in the world of photography is whether the images that stretch far beyond the normal expectations of a photo—photos that step beyond capturing things as they were– should be considered photographs or not. BUT … and this, for me, is a very essential “but” … no photograph is, by definition, just a recreation of what is there. A camera cannot photograph reality. All it can do is slice off a split second— or if a long exposure many moments— of something that occurred in that time period. It can never be the thing photographed. It is a representation of it. And it is selected representation of it. It requires a conscious effort to place something into a box of sorts—most often a rectangular frame. There is much intentionality. One cannot simply recreate things as they were in that moment. Thus, there is so, so, so, so much room for interpretation and, consequently, cameras and chemicals and Photoshop simply become tools. So, of course photography can be considered as art.

Is my work art? I have no idea. I am far too self-critical to ever make such a determination.

Are you married? If yes, honestly let me know your spouse’s role in development of your profession as a photographer.

My wife and I have been married for over twenty-four years. When I first thought about buying a DSLR back in 2007, my wife thought I was doing what all men do in their forties as they settle into their midlife crises: buy things they don’t really need in the hopes of filling a gap opened by the fact they are getting older (I was and remain far too poor to afford a sports car, so, apparently, a new DSLR was the best I could do). She was convinced that I would take a few pictures, get bored very quickly, and then toss the camera into the closet to be forgotten. My wife, like most human beings, rarely admits that she is wrong about anything, but she has made an exception for this. That said—she has been very helpful and very, very patient. When we go on vacation, she plans on me taking time out to go work on some photography— and we end up going certain places specifically because they are quite beautiful and photographable. My daughter, who is now twelve, is a little less patient with me!

I will add that I do not see photography as a profession. It is a practice, in the very Zen sense of that word. I do manage to work on a few projects that yield some money, and I have sold a number of prints and done a few solo-gallery shows, but I do not pursue photography for financial gain. I do it because I do it. It has become part of my nature. My profession is teaching English at City College of San Francisco. When I enter contests, I always enter as an amateur because I do not see myself as a working photographer. I am too self-critical to see myself as an artist. I leave that distinction to those who see my photographs.

Among your projects, which series or a single photograph is your favourite? What’s the story behind the project or photograph?

That is a nearly impossible question to ask. I do my best to not think in those ways, but if I have to choose one, I would choose Ishizuki. It represents one of the primary things I love about the practice of photography: encountering the unexpected. A viewer of the image cannot know my experience, but I look at that image and I recall how serendipitous it was that I encountered that tree. It sits above the rocky shoreline of a beach located in Crescent City, California in the United States. Crescent City is, in my opinion, a very lonely and depressing town. It is best known for two things: (1) a federal prison and (2) a tsunami that rolled in back in the 1960s and damaged a good part of the town. It is, however, surrounded by an abundant wealth of amazing nature (especially redwood forests and the ocean). And… this wonderfully beautiful pine tree sits there.

In the art form of bonsai, there is a style called ishizuki—which represents trees that grow on and/or over rocks. This is, of course, not an image of a bonsai tree— but the ishizuki-style is based on how trees grow on rocks in nature, the tree needing to adapt to a life of limited nutrients. They are very dramatic and very moving when you encounter them. A bonsai tree is a representation, a recreation of something that happens in nature. So is this photograph.

I also think one can feel some of the qualities of ma in this image.

What are some of the themes and concepts you explore in your works that are personally very close to you?

I am going to keep this answer brief and begin with one word: silence. I try to photograph the silence of solitude, the solitude of silence. There is a curious silence that resides in the folds of noise that surround us. One cannot, of course, hear that silence. But one, I do believe, can feel it and, I hope, photograph it. Or at least I am trying to.

If you could be any animal in the world, what animal would you be and why?

I would like to be a sea turtle and migrate across entire oceans and observe as much as I can in a lifetime.

What do you consider your biggest success in your career so far?

I must be entirely honest: I do not think about success and failure very much anymore. When I first began experimenting with a camera, I was concerned about finding success, about improving, about having my work appreciated by others. But in the past ten years, photography has become a practice for me.

Let me offer the following story to help illustrate what I mean: when a monk asked the Zen master Joshu to teach him, Joshu asked if the monk had eaten his rice. When the monk responded that he had, Joshu told him to wash his bowl. The monk was then enlightened.

This is a mysterious and strange story, and I am not qualified to speak of its lessons, but, despite my lack of enlightenment, I will say that the cleaning of the bowl is a practice. The goal is not to be the best bowl washer or to be a successful bowl washer. Why you are cleaning the bowl or what it means to clean the bowl are not things you need to understand. One simply cleans the bowl and does so after every meal. I do not see photography as a goal. I see it as a practice. I simply do it.

What makes a memorable photograph, in your opinion?

The truth, I believe, is that one is moved emotionally (and even spiritually) by a photograph whenever one is emotionally moved by a photograph. And, I suppose, a memorable photograph is one that moves someone emotionally (and spiritually). Those emotions can be as varied as joy, sadness, anger, hope, nostalgia, desire, inspiration, melancholy, etc. I do not, however, think one can intentionally create a photograph that will be considered memorable—one can only create a photograph that others will find memorable if others find it memorable. This is true for all art.

As I grow older (as of this interview I am now 52), I find myself less and less critical of art. To create something and share it with others is difficult. I might not like overly-saturated color images or I might be tired of looking at long-exposure architecture images, but I am not critical of these images, nor do I have any judgmental or ill feelings toward their creators. What something should or should not be is a very, very, very subjective perspective. Every year, here in the United States, the Grammy Awards and the Academy Awards give out accolades for films and movies that a group of people have determined are memorable. For me, most of these songs and films are dull and boring— but they are very, very popular. I am entirely disinterested in them. However, I do not wish to insult the people who made them.

We live in a world in which we are oversaturated by imagery. Billions of photographs are brought into existence every day. It is utterly and entirely overwhelming. But sometimes one encounters an image that clutches at one’s throat and makes one’s heart beat a little faster. These are images that manage to stand out from the billions and billions of other images, but their remarkableness is not grounded in the images themselves. It is grounded, instead, in the perceptions, reactions, and feelings of those who see them.

What is the relevance between minimalism and calm mind? Can we take minimalistic shots with a confused mind?

This is an interesting question. Personally, if I am confused or anxietous, I do not work on my practice of photography. I go for a walk and clear my mind. Sometimes, I will bring a camera along anyway, but my experience with image-making is almost always synonymous with quiet, with silence. It might be very noisy— waves crashing and birds peeping and screeching—but there is a silence that can be felt in that noise. This is what interests me—so this is what I work from.

Do you have any advice for aspiring photographers?

Do not listen to any advice from me!

What are your plans for the future?

I do not really plan for the future. I try, as best as I can, to live in the moment— but I fail often. That said—I would like to travel to Scotland and Ireland and then, later, to Japan. I plan to continue my practice of photography.

Thank you for your time. If you like to further explain any point for our readers, please go ahead.

I would like to thank you for this opportunity to share my thoughts and a few of my images. I am grateful for your generosity.